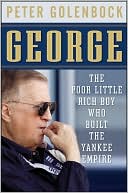

(John Wiley & Sons, 366 pages)

Bronx, N.Y., April 15, 2009 — You can almost sympathize with author Peter Golenbock when reading his just published biography of the Yankee owner titled George (John Wiley & Sons, 366 pages). In the preface, he shares with us that he was always a diehard Yankee fan, and that he was given access to the Yankee archives while doing research for his first book, Dynasty, a look at the Casey Stengel Yankees of the 1950s. One assumes the Yankees were not nearly as cooperative on this tome, given much of the criticism leveled at the Yankee owner in the books Mr. Golenbock coauthored with Yankee figures of the 1970s: Balls, with Graig Nettles; the self-titled Guidry; and more famously, Number 1, with Billy Martin; and The Bronx Zoo, with Sparky Lyle.

Golenbock trots out a lot of impressive background info, much of it obviously gleaned from his work with these stars 30 years ago. He also appears to have done his homework on Mr. Steinbrenner’s formative years, his career as a shipbuilding tycoon, his failed attempt to purchase the Indians and subsequent success in buying the Yankees, his indictment for making illegal campaign contributions to the Nixon presidential campaign, and the shameful chapter centering around his work with gambler Howie Spira to tar the reputation of his own player, Dave Winfield.

Golenbock paints the 1972 Yankees, the last team that played under CBS ownership, as a second-place team that had been restored to respectability by the hard work of Team President Michael Burke and General Manager Lee MacPhail. This portrayal has an element of truth to it, but the 1970 team alone achieved second place in Ralph Houk’s second tour of duty as Yankee manager from 1966-1973. The three years after the 1970 campaign, the team, the one George purchased, finished fourth.

In a two-sided portrayal Golenbock uses throughout the book, he quotes a Yankee employee around that time on new limited partner and newly named Team President Gabe Paul as “a doddering old fool who for forty years had been in baseball and had never been associated with a winner.” But once the new regime was in place, Paul is [correctly] credited with building a winner, while George is always the millstone around his neck. Of course, everyone knows that George had been “The Boss” since the day he took over in 1973, despite his protestations that he would not be an intrusive owner. He threw around lots of money, but virtually nobody who worked for him was happy. He derided his front-office staff and bore down mercilessly on the gradually crumbling Billy Martin through five tours of duty. And those were, largely, the good years. He set records for firing managers, general managers, and coaches. He would do anything to win, and wanted the credit for the wins as well. This is Golenbock’s premise, and it is one that cannot be dismissed. Without actually “diagnosing” George with either, the author floats descriptions of the traits found in Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder and Narcissistic Personality Disorder in a pre-Prologue the intent of which is obvious, and largely irrefutable.

Taking the two-sided Paul description as his template, the author gives us Martin as a petulant, self-involved, alcoholic brawler who had been fired by two organizations despite success on the field of play. But when he comes into contact with George, the portrayal softens into a tragic figure who was driven to behave badly by his boss. Both sides of Martin’s personality are true, of course, but more often than not just the latter is portrayed in confrontation with George. Similar dichotomies carry forward Golenbock’s point of view in discussions of Sparky Lyle, Reggie Jackson, Graig Nettles, Al Rosen, Goose Gossage, even Bucky Dent and Dallas Green.

It is well known that once the glory days of 1976-1978 were behind the team, there were a plethora of bad trades, most often surrendering young prospects for old players, a trend that was revisited after the 2001 World Series loss to the Diamondbacks. Golenbock rightly describes the dysfunction that led to the World Series drought the team experienced from 1981 through 1995 in this light, and few would disagree with him. He credits Gene Michael for righting the Yankee ship in the early nineties while George served his “lifetime” ban.

But one has to give the devil his due, so to speak, and until an almost fawning 10-page conclusion to the book, that is something the author rarely does. He characterizes the turbulence in the Yankee family in the late 70s as being the result of George’s will to buy the best players, but barely acknowledges the moves that worked. Catfish Hunter was better in Oakland, yes, but he led the team to the 1976 Series and was huge in the 1978 stretch run. Don Gullett may have been largely a bust, but it’s doubtful the 1977 crown would have been won without him. Worst of all, George is the mad scientist who created that 1977 madhouse, but Golenbock claims that “history does not back up [that] legend” that Steinbrenner insisted on signing Jackson because he would be a winner and a draw. It is no doubt true that Sparky Lyle rightfully felt betrayed after his 1977 Cy Young season, but the recent elevation of Goose Gossage to the Hall of Fame bespeaks the fact that the purchase of his contract paid off as well. Graig Nettles had just been acquired in trade, but Chris Chambliss, Ed Figueroa, Mike Torrez, Mickey Rivers, and Bucky Dent, to name a few, came after the Steinbrenner team was in place.

And when the winning stopped, Golenbock picks up speed. He criticizes the impetuous trade for Roy Smalley to play shortstop in 1982 when “they already had Bucky Dent,” but Dent had hit .238 in 73 games in 1981 and was down to .169 with no home runs and nine rbi’s in the 59 games he played in ’82. Later in that frustrating decade the author derides Steibrenner’s criticism of Manager Dallas Green’s overuse of his starters, even though a 150-plus-pitch outing by young Al Leiter undoubtedly led to this lefthander’s shoulder problems for years. We are told that “after [pitching coach Mark] Connor was fired, [Ed] Whitson suddenly lost his effectiveness,” but that unfortunate righthander was 1-6 on June 6, 1985, his only season in Pinstripes, a year he finished up at 10-8. The owner is likewise taken to task for trading Rick Rhoden and Jack Clark away, while it’s well acknowledged that the moves to acquire those two players were the more unfortunate ones.

Mr. Golenback certainly had some ripe sources for his descriptions of the early George years, and we’ll assume he did the research and that his descriptions of Steinbrenner’s pre-Yankee life are accurate. Would that he could have filled in many of the blanks over the last 30 years with similar careful research and vetting. But alas, that is not the case. There are some glaring errors in the book. His Yankee history intro identifies Ed Barrow as Yankee General Manager when that ex-Red Sox manager’s actual title was Business Manager; and the names of Yankee prospects Brien (Brian) Taylor, Marty Janzen (Jansen) are misspelled, as is that of Mike DeJean (DeJong), the latter identified simply because he was traded away to Colorado to bring current Yankee Manager Joe Girardi on board as a catcher back in 1995. But we leave the worst for last: Frank Layden is rightfully honored for his years coaching the NBA’s Utah Jazz among other things, but not in this book. He never played organ for the Yankees. Those chores were handled for more than 35 years by the late Eddie Layton.

Also disturbing are some of the offhand descriptions and judgements regarding what took place on the field of play, and in transactions. He describes an ugly 1977 dugout confrontation between Billy Martin and Reggie Jackson on national TV as having been precipitated by Jackson’s lackadaisical fielding of a Jim Rice ground single, when it was a short fly base hit, and depicts Chris Chambliss’s stirring pennant-winning home run in Game 5 of the 1976 ALCS as a line drive, when in fact it was a high fly that almost scraped the back of the Yankee Stadium right field wall on its downward flight. And while I totally agree with his bleak assessment of the movie The Scout, largely filmed in Yankee Stadium, I am painfully aware that it did not go straight to video. The hours and money I wasted in the movie theater are not easily forgotten. He mischaracterizes the Alex Rodriguez/Scott Boras rift after the 2007 season as a player firing of his agent, and he labels the acquisition of Ivan Rodriguez last summer an “inspired” move. Not so.

There is no doubt that George continued to rule with an iron fist in the Joe Torre years, behaving like a bully when he did not get his way. Golenbock correctly points out that even after George hired Torre to be his new manager, he went back on his word and offered the position to Buck Showalter, if he would only return. But George is not credited with going along with Arthur Richman’s recommendation that he hire Joe as manager, something that allowed him to increase the AL pennants during his ownership to 10 and the World Series Championships to six. Torre was largely left out of the celebrations that closed the old Stadium last year, and a read between the lines of his new book reveals his dismay with the way he was treated by the whole Steinbrenner family. His longtime much-beloved bench coach Don Zimmer has nothing good to say about George to this day. But can the break in their relationship have been any worse than the long rift between George and Yankee Hall of Famer and ex-Manager Yogi Berra, which has now been healed for some time?

The 10-page list of some of Mr. Steinbrenner’s nicer accomplishments (which fails to mention the Yankee team flight to and playing an exhibition game at a shellshocked Virginia Tech campus in early 2008, by the way) at the book’s end notwithstanding, Mr. Golenbock would have a better book if he acknowledged a few more of George’s successful decisions over the years. No matter how difficult it may have been serving under Steinbrenner over the last 36 years, he made a lot of people famous and rich because he did do some things right. An old man deserves that recognition.

YANKEE BASEBALL!!!